Brule River protected: Goodbye railroad crossing, hello trout and salmon.

By John Myers, Duluth News Tribune – November 04, 2023

By John Myers, Duluth News Tribune – November 04, 2023

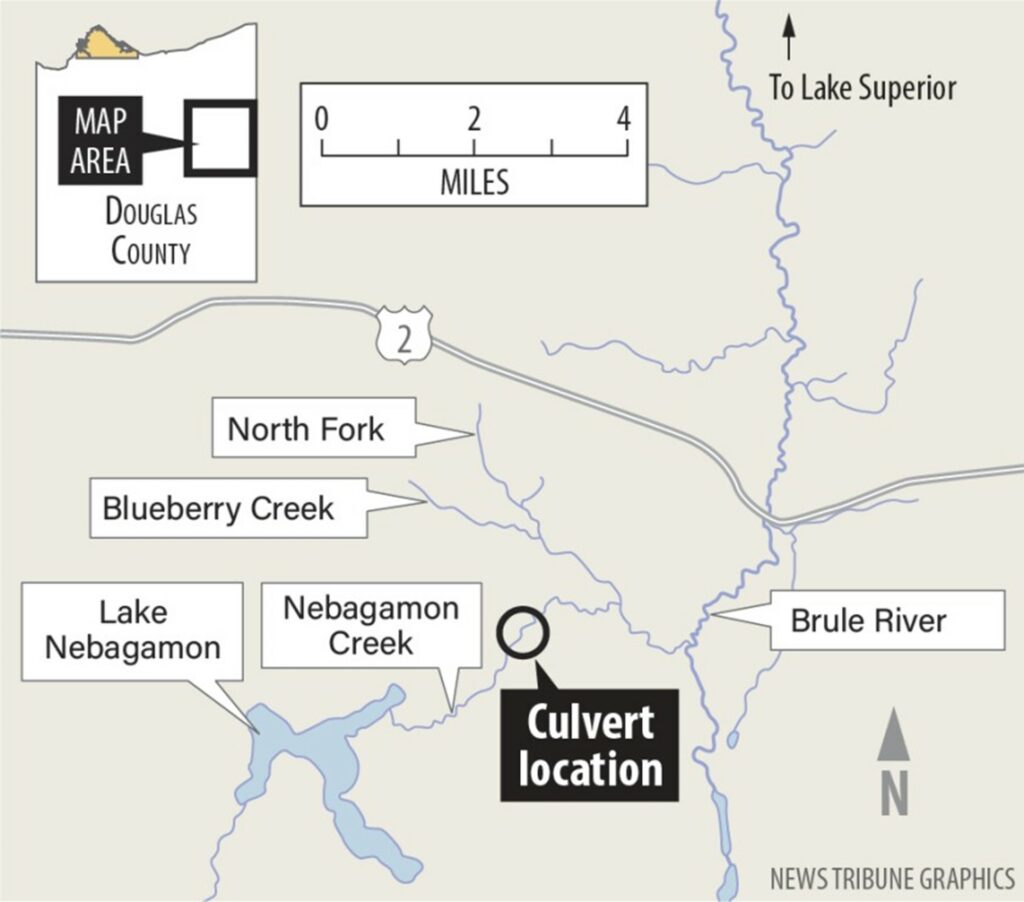

A crumbling, long-abandoned crossing over Nebagamon Creek has been removed, averting a washout disaster for the storied Brule River.

With a blocked culvert and abandoned railroad crossing removed, Nebagamon Creek now flows freely and unobstructed from Lake Nebagamon to the Brule River. A $770,000 project completed recently may have saved miles of fish spawning habitat along the creek and downstream river from a major washout.

Photo Contributed / Dennis Pratt

BRULE — A crumbling railroad grade abandoned nearly a century ago and choking Nebagamon Creek, threatening to pour sediment into the Bois Brule River, has finally been removed in a massive project aimed at protecting fish spawning habitat.

Years in the works, the $770,000 effort was completed in October, overseen by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources with funding from a potpourri of state and federal grants as well as gifts from nonprofit groups and even private donations.

Before the recent project, a long-abandoned railroad crossing over Nebagamon Creek downstream from Lake Nebagamon had nearly plugged entirely, creating a damming effect that could have created a major washout, sending a torrent of water, sand and sediment downstream to the Brule River. The culvert and railroad grade were recently removed along the creek, creating a natural stream channel and removing the obstruction.

Photo Contributed / Dennis Pratt

Imagine a 38-foot-tall dam that suddenly broke open, which was what would have happened at some point. The volume of sand that would have washed from the banks along Nebagamon Creek with all that water would have been disastrous to the Brule.

Dennis Pratt, president of Brule River Sportsmen’s Club

The long-silenced Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic Railway hadn’t been used since 1934, with the tracks torn up in 1936. But a 110-foot-long, 12-foot-diameter culvert that had carried Nebagamon Creek under the railroad tracks was eroding, with concrete supports crumbling into the creek, effectively damming up much of the flow for the past decade.

The project essentially rebuilt and naturalized 500 feet of Nebagamon Creek, which is the largest tributary to the Brule River. The Brule is among the best spawning rivers for Lake Superior trout and salmon anywhere on the lake.

Gary Meader / Duluth News Tribune

The fear was that the sand and silt that had been building up for decades behind the railroad crossing would suddenly wash out and push downstream, covering sensitive spawning beds used by steelhead rainbow trout, Chinook salmon and brook trout, said Paul Piszczek, DNR fisheries biologist who specializes in Lake Superior streams.

“It would have been a disaster for all that material to wash down and cover up some really good spawning areas in the creek, but possibly even in the Brule itself.’’ Piszczek said.

The old railroad crossing was about 1 mile downstream from Lake Nebagamon and just over 4 miles upstream from the Brule. Not only does the project help avert a sedimentation disaster, but it opens up additional spawning habitat in the creek leading up to the lake and beyond, including small tributary streams that lead into the lake.

Opening day saw thigh-deep snow in places along the river but otherwise decent conditions.

“There’s a lot of great upstream habit potential there now that this barrier has been removed,’’ Piszczek said, noting that coho salmon and brown trout also may move farther up the creek now that they have the chance.

The project took years to plan, including more than two years to track down potential owners of the land where the crossing is located. Once that was done, permission was secured, a hydrological study was completed and the proper environmental permits were approved, and the work began over the summer.

An aerial photo of the stretch of Nebagamon Creek that was restored to a natural channel after a $770,000 project to remove an old railroad grade crossing and collapsing culvert that had nearly dammed the flow of the creek. Fish now have a clear path from Lake Superior, up the Brule River and Nebagamon Creek and even beyond Lake Nebagamon.

Photo Contributed / Dennis Pratt

The work was completed Sept. 22-25, just before torrential rains fell across the region, including more than 7 inches in some places. That event may have been the final straw for the already sloughing and crumbling century-old concrete and earthen railroad grade. September was among the wettest months on record, with more than 10 inches of rain recorded in Duluth, 7 inches more than normal.

Dave Zentner, an avid trout angler and longtime member of the Duluth chapter of the Izaak Walton League of America, praised Piszczek’s efforts at sticking with the project even as government red tape and ownership issues delayed it for years.

“He really deserves credit for sticking with it and finally making this happen.’’ Zentner said.

Dennis Pratt, president of the Brule River Sportsmen’s Club and a former fisheries biologist, said a single flood event, like what might have been spurred by the September downpours, would carry away many tens of thousands of cubic yards of sand as it washed away the sand-laden banks of Nebagamon Creek and its valley walls.

Dumping this much sand into the Brule would have created a huge sand slug moving down the Brule, eventually covering and destroying trout habitat as it went. Aquatic insect populations would plummet and trout spawning and habitat areas would be destroyed.

“Imagine a 38-foot-tall dam that suddenly broke open, which was what would have happened at some point.’’ Pratt said. “The volume of sand that would have washed from the banks along Nebagamon Creek with all that water would have been disastrous to the Brule.”

Major funding for the project came from a federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative grant in addition to fish passage funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and trout stamp funding from the DNR, with additional grants and donations coming from multiple conservation groups and private citizens.

“Someone even started a GoFundMe site for this project.’’ Piszczek said. “It’s a big deal to people who fish the Brule.”